Deviance as an historical artefact: a scoping review of psychological studies of body modification

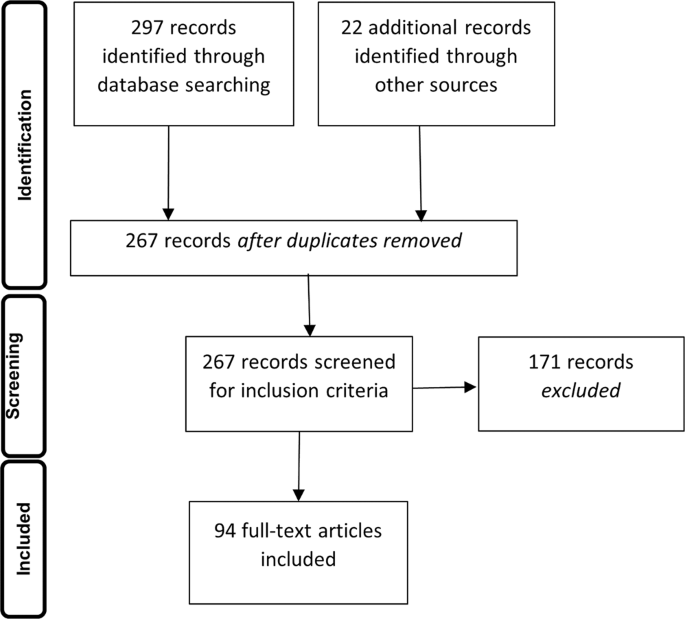

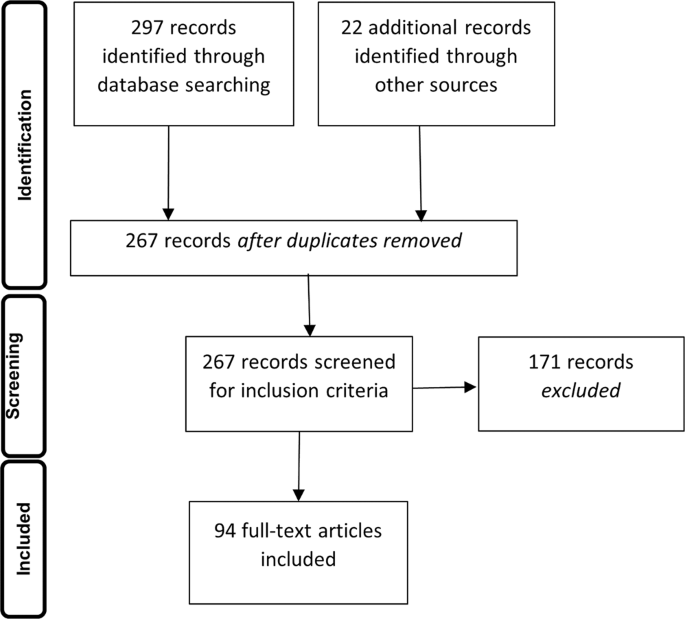

Body modification is a blanket term for tattooing, piercing, scarring, cutting, and other forms of bodily alteration generally associated with fashion, identity, or cultural markings. Body modifications like tattooing and piercing have become so common in industrialised regions of the world that what were once viewed as marks of abnormality are now considered normal. However, the psychological motivations for body modification practices are still being investigated regarding deviance or risky behaviours, contributing to a sense in the academic literature that body modifications are both normal and deviant. We explored this inconsistency by conducting a scoping review of the psychological literature on body modifications under the assumption that the psychological and psychiatric disciplines set the standard for related research. We searched for articles in available online databases and retained those published in psychology journals or interdisciplinary journals where at least one author is affiliated with a Psychology or Psychiatry programme (N = 94). We coded and tabulated the articles thematically, identifying five categories and ten subcategories. The most common category frames body modifications in general terms of risk, but other categories include health, identity, credibility/employability, and fashion/attractiveness. Trends in psychology studies seem to follow the shifting emphasis in the discipline from a clinical orientation regarding normality and abnormality to more complex social psychological approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

The sources and consequences of sexual objectification

Article 25 May 2023

Distilling the concept of authenticity

Article 28 June 2024

The role of body image dissatisfaction in the relationship between body size and disordered eating and self-harm: complimentary Mendelian randomization and mediation analyses

Article Open access 13 August 2024

Introduction

Body modifications in general and tattooing in particular have increased in popularity steadily over the last 50 years in England, the United States, and other industrialised countries (Burns, 2019; DeMello, 2000; Statista Research Department, 2021). The culture around tattooing and other body modifications in the developed and developing countries has shifted rapidly; however, attitudes can be resistant to change. Moreover, while pictures of tattoos and other body modifications populate Instagram and other visually oriented social media platforms, a recent opinion piece from The Times that enjoyed a wide circulation during the writing of this article (“Seeing tattoos makes me feel physically sick: Ubiquity of body art is born out of an existential crisis of humanity in the post-religious world” by Melanie Phillips, 2022) supports the notion that mainstream attitudes may lag behind cultural portrayals.

There are numerous means to permanently modify the body (Table 1), so this is potentially a vast literature. The contemporary history of all body modifications is beyond the scope of this article, but we recommend interested readers consult Pitts-Taylor (2003), Eubanks (1996), Vale and Juno (1989) as but a few examples. However, the body modification literature focuses primarily on tattooing, so a short history at least of tattooing may be illustrative.

Our team of five co-authors met weekly over the course of a year to read and discuss coding of articles. First, we divided the articles up among our team, read 5–10 each, and identified salient themes. We then met to discuss the themes we had identified and repeated this process multiple times. Through this iterative process, we determined that the best way to assess the corpus of psychological studies of body modifications would be to categorise them based on their stated or implied study objectives. Therefore, we reshuffled the articles and divided them evenly among the five team members, and each team member categorised the articles based on the specific or apparent objectives of each article’s authors. We then met as a team and discussed the coding of each article; if the team was not in agreement, we discussed until we reached consensus on the final set of categories and subcategories and the categories to which each article should be assigned. Ad hoc articles discovered during the process were reviewed together and assigned categories by the entire team.

In addition to themes, we coded articles based the demographic focus of the study (e.g., college students, women, prisoners, etc.), what country the study took place in and whether they were in-person or online studies, the methods used, and gaps or critiques of the literature identified by the authors. After coding the articles, we reread the articles within each section in order of publication date to see what theory authors were drawing on and, a task which elicited some additional articles and shed light on temporal changes in Psychology as a discipline.

Results

We identified 69 articles about tattooing only, 18 about tattooing and piercing, 6 about piercing only, and one article about multiple forms of body modifications, including scarification, tattooing, piercing, and other forms.

Table 2 outlines the categories that most appropriately characterise the objectives of each article. The most common sample among psychology articles examining body modifications was a general Euro-American population (n = 33), followed by college students (n = 22), women only (n = 9, including one that sampled women only but asked about men), prisoners or convicts (n = 7), patients (n = 6), youth (n = 4), specific job roles (n = 4), general tattooed population (n = 3), case studies (n = 2), men only (n = 2, one sampled men but asked about women only), and multiple populations (n = 2).

Table 2 Peer-reviewed research articles about body modification by psychologist/psychiatrists or published in psychology/psychiatry journals (N = 94).

The most common objective among psychology articles about body modifications (n = 36 or 38% of total sample) was to test for underlying dysfunction or tendencies toward deviant behaviour associated with body modifications. Among those, 25% examined correlations between past behaviours or experiences and body modifications, whereas 41% examined current behaviours or sought to predict future behaviour.

The second most common objective was an effort to assess how tattooed (not body modifications in general) people are perceived, characterised, and treated by others (n = 31 or 32% of total sample). Within this category, we identified six sub-objectives, including perceptions for employment or when at work (32% of category), if tattooing impacts trustworthiness (12% of category), if tattooed people are worth helping (9% of category), and if tattooing influences perceived attractiveness (6% of category).

The third most common objective was a general exploration of why people engage in body modifications (n = 18 or 19% of total sample). Among those, five articles (27% of category) explored the possibility that tattooed people are fundamentally different from non-tattooed people.

The fourth most common objective of psychological studies of body modifications was to explore if tattoos impact health (n = 15 or 16% of total sample). Two articles (13% of category) concluded that tattoos help health, whereas authors of nine articles (67% of category) investigated whether tattoos indicate poor health.

The least common objective among psychological studies of body modifications was to explore them as aspects of identity (n = 9 or 9% of total sample). We identified one subcategory for those focused on subjective feelings of attractiveness vis-à-vis their body modifications with two articles in this subcategory (22% of category).

Discussion

In this article, we provide an overview of peer-reviewed, primary source articles on voluntary, invasive body modifications published in psychology journals or journal articles that featured one or more authors whose affiliation was a Psychology or Psychiatry programme. Our search was intended to be a comprehensive assessment of sources available through online databases. The identified studies range widely in terms of study characteristics, methodologies, and locations. A notable finding was that there were few psychological/psychiatric studies of body modifications beyond those related to tattooing. Most of the body modifications outlined in Table 1 are rare, so, if the objective of the studies was to identify aberration, it might seem intuitive to study the rates and motivations for engaging in rare body modifications. However, our main finding is that psychological/psychiatric studies of tattooing have been rooted in traditional abnormal psychology and have tended to reify stigma through their research design. This is true even when the author objectives are to demonstrate that modified people are not deviant or stigmatised. There were very few psychological studies of body modifications outside of clinical or penal settings until the twenty-first century, suggesting changing perspectives in the fields of psychology and psychiatry.

Body modifications and deviance

Most psychological studies of body modifications seem to derive from the field of abnormal and clinical psychology. The earliest publications in our sample (Duncan, 1989; Edgerton and Dingman, 1963; Ferguson-Rayport et al., 1955; Taylor, 1974) are studies of prisoners and psychiatric patients that provide clues as to the shift from popular practice to stigma. Ferguson-Rayport et al. (1955) review numerous studies indicating, for instance, that tattooed people were more likely to be denied military enlistment or that tattooing was linked with homosexual behaviour in correctional institutions and reform schools. Furthermore, the authors hold “that the tattoo expresses masochistic-exhibitionistic drives and directly illustrates and encourages homosexual activity…tattoos are often compensatory in individuals poorly adjusted, especially in the sexual sphere” (Ferguson-Rayport et al., 1955, p. 116). Such studies appear to reconstitute or extend earlier criminological efforts to taxonomically categorise potential for deviance. Edgerton and Dingman (1963), by contrast, conducted a qualitative exploration of tattooing among mental hospital patients to determine if, as suggested by anthropological studies of non-Euro-american tattoo practices, marking oneself permanently is an important aspect of identity-formation.

Though several standardised methods for assessing personality were developed in the first half of the twentieth century (Butcher, 2009), they do not appear to have been used in body modification research until the 1970s, when research sought to determine if tattooed prisoners and psychiatric patients were psychologically different than non-tattooed counterparts. For example, Taylor (1974) indicates significant differences between tattooed and non-tattooed individuals but does not provide any statistics to support this. By contrast, Duncan (1989) and other forensic studies (e.g., Birmingham et al., 1999) find negative or unhealthy behaviour associated variously with both modified and non-modified inmates.

Within the clinical psychology literature, penal or forensic studies seem to highlight body modifications as potential indicators of deviance or mental disorder, whereas studies relating to outpatient disorders (e.g., Bui et al., 2013; Caplan et al., 1996; Claes et al., 2005) suggest that body modifications may be sublimations of tendencies toward self-harm or other negative behaviour. Cardasis et al. (2008) notes a justification for this approach, pointing out that a primary feature of anti-social personality disorder is a need to seek immediate gratification and external stimulation to alleviate anxiety or discomfort. Buss and Hodges (2017) suggest the search for associations between body modifications and deviance is rooted in religious proscriptions against marking one’s body (see Scheinfeld, 2007 for examples) that were employed in the colonial era of empire-building to distinguish the “civilised” from “savage”. Multiple studies (e.g., Aizenman and Jensen, 2007; Ceylan et al., 2019; Stirn and Hinz, 2008; Stirn et al., 2011; Swami et al., 2015; Vizgaitis and Lenzenweger, 2019) conflate body modifications and non-suicidal self-injury or trauma and suggest that body modifications may be indicators of other anti-social tendencies.

Others (e.g., Drews et al., 2000) simply choose to emphasise terms like “risky” behaviour over analogous but differently valanced terms like “adventurous” or to emphasise the potential risks of tattooing (e.g., Koch, Roberts, Cannon, et al., 2005). Though poor-quality tattooing can certainly be dangerous (Kluger, 2015; Kluger and Koljonen, 2012), the chances of encountering tattoo-related medical complications in the current era is low, and there is some evidence to suggest that past fears over blood-borne pathogen transmission have been greater than the actual incidence of such tattoo-related medical complications (Jelinski, 2018; Lynn et al., 2019).

Body modifications and social interactions

All other psychological studies seem to wrestle with the changing status of body modifications as an emerging or “new” normal. We identified what could be called a “general” category of social psychology studies of body modifications, seeking explanations for how modified people are perceived and how people with modifications are treated (e.g., Drews et al., 2000; Galbarczyk et al., 2020; Galbarczyk and Ziomkiewicz, 2017; Hawkes et al., 2004; Martino, 2008; Martino and Lester, 2011; Miłkowska et al., 2018; Resenhoeft et al., 2008; Wohlrab et al., 2009a, 2009b). An a priori assumption undergirding these studies is that body modifications have been historically stigmatised, and stigma may persist in interpersonal interactions.

A paradigm shift in body modification research seems to have occurred from the 1970s through the 2000s, with psychology the last to come around. This shift makes the fields of psychology and psychiatry appear to be out of step, but it is worth remembering that clinical psychology is historically grounded in the deficit-oriented biomedical model, which is focused on healing illness and diagnosing disfunction (Sheridan and Radmacher, 1992). Whereas body modifications as normal behaviours have long been subjects of study for allied social sciences like anthropology and sociology, social psychology was still developing as a discipline in the 1950s and 1960s (Stangor, 2014); social psychology research on body modifications seems to have only gotten underway beginning in the twenty-first century.

Three areas within social psychology seem particularly focused on body modifications: industrial, health, and evolutionary psychology. Industrial or occupational psychology is a subfield of social psychology concerned with human relations in work-related settings. A common theme in the concern over body modifications is how visible modifications will influence employability (e.g., Burgess and Clark, 2010; Dillingh et al., 2020; Flanagan and Lewis, 2019; Hauke-Forman et al., 2021; Tews et al., 2020; Thielgen et al., 2020; Timming et al., 2017; Timming, 2015; 2017; Wiseman, 2010b). Some studies relate to particular circumstances wherein bias toward body modifications could undermine interactions beyond employment status, such as in the courtroom (e.g., Funk and Todorov, 2013) or classroom (Wiseman, 2010b) or based on the specific imagery of a person’s tattoos (e.g., Timming and Perrett, 2016).

Among health psychologists, there is concern that the association of body modifications with abnormality might lead to people in marginal groups being in “double jeopardy” (e.g., Zestcott et al., 2017; Zestcott and Stone, 2019; Zestcott et al., 2018). Another line of research taking the opposite tack comes out of evolutionary psychology, arguably a subfield of social psychology (Kruglanski and Wolfgang, 2012). The evolutionary perspective suggests that well-healed modifications may function as external indicators of good underlying health. This hypothesis is tested by exploring how modifications are perceived by observers in terms of attractiveness and health as adaptive indicators of partner suitability (e.g., Galbarczyk et al., 2020; Galbarczyk and Ziomkiewicz, 2017; Miłkowska et al., 2018; Wohlrab et al., 2009a, 2009b).

Body modifications and health

Most studies of body modifications and health do not focus on the double jeopardy of marginalised groups or evolutionary signalling theory. Most are grounded in abnormal psychology studies of the 1980s and 1990s and therefore collect data on mental/physical health and substance use even when their study objective is ostensibly about body modifications and other topics (e.g., Dillingh et al., 2020). Some reframe the focus on abnormality and instead use body modifications as indications of “impulsivity” or tendencies toward “sensation-seeking”, which are themselves considered risk factors for some abnormalities (e.g., Kertzman et al., 2013; Mortensen et al., 2019). One study uncritically claims that tattoos and premarital sex are “categorically deviant in a traditional sense but are typical among college students” as justification for a correlational study (Koch et al., 2005, p. 887). Another study by the same group of authors (Koch et al., 2005) explores beliefs about the health and social dangers of tattoos, as though tattoos are more dangerous than current evidence suggests (cf. Jelinski, 2018; Lynn and Medeiros, 2017). Some studies note that, not only are body modifications different in how they are adopted and used, but each type of body modification also has variation. Tattooing varies by design, extent, body location and other factors that are “read” by interlocutors and observers in the explicit and implicit communication of social interactions (Geller et al., 2020). Furthermore, as body modifications become more popular in developing countries due to media exposure, psychological studies conducted by researchers in those countries replicate the type of mental health studies conducted previously in Europe and the United States (e.g., Geller et al., 2020; Kertzman et al., 2019a, 2019b; Kertzman et al., 2013; Pajor et al., 2015).

By contrast, other psychological studies acknowledge that, among body modifications, piercing and tattooing is “becoming mainstream” (Hill et al., 2016, p. 246) and explore body modifications from developmental psychology perspectives. Some such studies explore body modifications as means of improving self-esteem or one’s own body image (e.g., Hill et al., 2016; Kertzman et al., 2019a), as a form of healing from trauma (e.g., Maxwell et al., 2020), or as an option for healthy lifestyles (Huxley and Grogan, 2005). One unique study (Thompson, 2015) explored associations between tattooing and “generativity”, a concept associated with prosocial behaviour.

Tattooing and identity

Beyond the importance of deviance, health, and the social roles of tattoos, researchers identified the role and materiality of body modifications in identity and personal aesthetics. We note two general trends concerning the role of body modifications specifically in emerging identities and perceptions of attractiveness. We distinguished studies of identity as those in which researchers largely ask questions that explore how those with body modifications view themselves. Within these articles, there are two further distinctions of identity, where researchers identify the underlying meanings attributed to body modifications (e.g., Mun et al., 2012; Tiggemann and Golder, 2006; Tiggemann and Hopkins, 2011) and modifications as identity signalling to social others (e.g., Bergh et al., 2017; Dillingh et al., 2020; Molloy and Wagstaff, 2021; Mun et al., 2012; Skegg et al., 2007).

Neither identity nor the meanings people attribute to their tattoos are fixed in time (Howson, 2013), and researchers try to convey this complexity by collecting diachronic information pertaining to the meaning of tattoos (the narrative story behind the tattoo), though the recurrent theme within these studies concerns change to meanings (e.g., Mun et al., 2012; Tiggemann and Golder, 2006; Tiggemann and Hopkins, 2011). For example, Mun et al. (2012) note that some tattoo meanings shift over time, reflecting life transitions, such as tattoos that commemorate past relationships or affiliations (e.g., gang imagery) (e.g., Mun et al., 2012). The through line of these identity-oriented articles largely point to individuals using tattoos as markers of individuality that reflect multi-faceted, densely layered meanings.

Tattoos can also be the material manifestations of certain types of communal (e.g., Edgerton and Dingman, 1963), ethnic (e.g., Skegg et al., 2007), or gender identities (e.g., Galbarczyk and Ziomkiewicz, 2017). Within this scoping review, several of the developmental psychology articles focus largely on tattoos as materialising and signalling identity (e.g., Dillingh et al., 2020; Mun et al., 2012; Skegg et al., 2007). Although many individuals use tattoos to signal identity through self-presentation (e.g., Molloy and Wagstaff, 2021; Mun et al., 2012; Tiggemann and Golder, 2006; Tiggemann and Hopkins, 2011), this requires understanding the meaning of a tattoo’s visibility (can it be seen by casual observer or only in intimate circumstances?) (Dillingh et al., 2020). People present themselves in myriad situations and environments in their everyday lives, requiring different “selves” to be presented accordingly; tattoos signalling identity can therefore take many forms, and psychologists suggest that people make these decisions based on life experiences, social settings, and other reasons in order to embody the identities they want to present (e.g., Dillingh et al., 2020; Mun et al., 2012; Tiggemann and Golder, 2006; Tiggemann and Hopkins, 2011).

Limitations

Our analysis unfortunately reinforces the “siloing” of academic disciplines for a subject that is in fact very interdisciplinary in nature and has been studied from numerous vantages we did not address. However, the historical trend we have noted was not apparent until we conducted this analysis, and it is important to distinguish the contributions various disciplines can make to body modification research and what strengths and weaknesses may be inherent to respective disciplinary approaches. This analysis may also suggest that psychologists and psychiatrists are alone in drawing parallels between body modification and risk behaviour or stigma, but this is also far from true. Nevertheless, forensic research conducted by psychologists, psychiatrists, and criminologists prevails among early body modification studies. Future research should include similar treatments for other relevant disciplines (e.g., anthropology, sociology, biology, criminology, nursing, dermatology, etc.).

Conclusions

The psychological studies examined in our review span the period 1955–2021. Early studies imply moral parallelisms by comparing body modification tendencies to religiosity, sexual activity, sexuality, alcohol or drug use, etc. This approach seems to derive from the legacy of nineteenth century criminology, which in turn appears based on a previous stigmatisation of irreversible body alterations among European cultures (Caplan, 1997). Lane (2014) makes a similar observation, suggesting that nineteenth century criminologists thought of criminals as atavistic and tattoos as indications of their reversion to primitiveness. This approach is continued in contemporary research when studying body modification in clinical populations, as well as among adolescents, seeking explanations for past behaviours and for “tells” of future tendencies (Lane, 2014).

In conclusion, we found no legitimate motivation for the inherent stigma towards individuals who voluntarily modify their bodies. Instead, this is an historically particular legacy of the social sciences and their various developments. Continued focus on deviance or risk regarding body modifications directly (i.e., not including intervening assessments of personality traits) seems a desperate assertion of an antiquated or atypical moral stance that now rings as somewhat absurd. Future research should continue to integrate perspectives from allied disciplines to gain a more accurate and nuanced view of the psychology of body modifications. The psychobiosocial approach taken in several twenty-first century health psychology studies—e.g., “double jeopardy” among marginalised populations or how tattoos are used by some people to help heal from past traumas—are promising research directions. The psychological study of modified people has primarily focused on tattooing, and future research should also acknowledge the variation of invasive voluntary modifications as they become more popular and available. Furthermore, technological advances are making tattoos less permanent while opening biomedicine to other forms of tattooing, which promise further shifts in how we study the psychology of body modifications. Emerging research using new methods and technology and that acknowledges how past research design reify the stigma they purport to study promises suggests a new paradigm of body modification investigations on the horizon.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this research as no data were generated or analysed.

References

- Aizenman M, Jensen MAC (2007) Speaking through the body: the incidence of self‐injury, piercing, and tattooing among college students. J College Counsel 10(1):27–43 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Anderson M, Sansone RA (2003) Tattooing as a means of acute affect regulation. Clin Psychol & Psychother 10(5):316–318 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Angel G (2017) Recovering the nineteenth-century European tattoo. In: Ancient ink: the Archaeology of tattooing. (pp. 107–129). Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Antoszewski B, Sitek A, Fijałkowska M, Kasielska A, Kruk-Jeromin J (2010) Tattooing and body piercing—what motivates you to do it. Int J Soc Psychiatry 56(5):471. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764009106253ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Atkinson M (2004) Tattooing and civilizing processes: body modification as self-control. Can Rev Sociol 41(2):125. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2004.tb02173.xArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ball J, Elsner RJ (2017) Changes in aesthetic appeal of tattoos are influenced by the attractiveness of female models. Psychology 7(4):247–252 Google Scholar

- Bergh L, Jordaan J, Lombard E, Naude L, van Zyl J (2017) Social media, permanence, and tattooed students: the case for personal, personal branding. Crit Arts 31(4):1–17 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Birmingham L, Mason D, Grubin D (1999) The psychiatric implications of visible tattoos in an adult male prison population. J Forens Psychiatry 10(3):687–695 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bradley J (2000) Body commodification? Class and tattoos in Victorian Britain. In: Caplan J (ed.), Written on the body: the tattoo in European and American History . Princeton University Press. p. 136

- Broussard KA, Harton HC (2018) Tattoo or taboo? Tattoo stigma and negative attitudes toward tattooed individuals. J Soc Psychol 158(5):521–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1373622ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Bui E, Rodgers R, Simon NM, Jehel L, Metcalf CA, Birmes P, Schmitt L (2013) Body piercings and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in young adults. Stress Health 29(1):70–74 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Burgess M, Clark L (2010) Do the “savage origins” of tattoos cast a prejudicial shadow on contemporary tattooed individuals? J Appl Soc Psychol 40(3):746–764 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Burns DL (2019) Social media and tattoo culture in consideration of gender. In: Bodinger-deUriante C (ed.). Interfacing ourselves: living in the digital age. Routledge. pp. 28–42

- Buss L, Hodges K (2017) Marked: tattoo as an expression of psyche. Psychol Perspect 60(1):4–38 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Butcher JN (2009) Clinical personality assessment: History, evolution, contemporary models, and practical applications. Oxford handbook of personality assessment. Oxford University Press. pp. 5–21

- Caplan J (1997) ‘Speaking scars’: the tattoo in popular practice and medico-legal debate in nineteenth-century Europe. In: History Workshop Journal, No. 44, Autumn, 1997, p. 129

- Caplan J (2000a) ‘National Tattooing’: traditions of tattooing in nineteenth-century Europe. In: Caplan J (ed.), Written on the Body: The Tattoo in European and American History. Princeton University Press. pp. 156–173

- Caplan J (ed.) (2000b). Written on the body: the tattoo in European and American history. Princeton University Press

- Caplan R, Komaromi J, Rhodes M (1996) Obsessive–compulsive disorder, tattooing and bizarre sexual practices. Br J Psychiatry 168(3):379–380 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Cardasis W, Huth‐Bocks A, Silk KR (2008) Tattoos and antisocial personality disorder. Pers Mental Health 2(3):171–182 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Carroll L, Anderson R (2002) Body piercing, tattooing, self-esteem, and body investment in adolescent girls. Adolescence 37(147):627 Google Scholar

- Ceylan MF, Hesapcioglu ST, Kasak M, Yavas CP (2019) High prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury, tattoos, and psychiatric comorbidity among male adolescent prisoners and their sociodemographic characteristics. Asian J Psychiatry 43:45–49 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H (2005) Self‐care versus self‐harm: Piercing, tattooing, and self‐injuring in eating disorders. Eur Eat Disorder Rev 13(1):11–18 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- DeMello M (2000) Bodies of inscription: A cultural history of the modern tattoo community. Duke University Press. http://scout.lib.ua.edu.libdata.lib.ua.edu/?itemid=library/m/voyager1040732

- Department SR (2021, 1 June). Body modification in the United States-Statistics & Facts. Statista. Retrieved 20 May from https://www.statista.com/topics/5135/body-modification-in-the-us/#topicHeader__wrapper

- Deter-Wolf A, Robitaille B, Krutak L, Galliot S (2016) The world’s oldest tattoos. J Archaeol Sci Rep 5:19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.11.007ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Dhossche D, Snell KS, Larder S (2000) A case-control study of tattoos in young suicide victims as a possible marker of risk. J Affect Disord 59(2):165–168 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Dillingh R, Kooreman P, Potters J (2020) Tattoos, lifestyle, and the labor market. Labour 34(2):191–214 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Douglas B (2005) Cureous figures: European voyagers and tatau/tattoo in Polynesia, 1595-1800. In: Thomas N, Cole A, Douglas B (eds.), Tattoo: Bodies, art and exchange in the Pacific and the West. Duke University Press. pp. 33–52

- Drews DR, Allison CK, Probst JR (2000) Behavioral and self-concept differences in tattooed and nontattooed college students. Psychol Rep 86(2):475–481 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Duncan DF (1989) MMPI scores of tattooed and untattooed prisoners. Psychol Rep 65(2):685–686 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Edgerton RB, Dingman HF (1963) Tattooing and identity. Int J Soc Psychiatry 9(2):143. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076406300900211ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ekinci O, Topcuoglu V, Sabuncuoglu O, Berkem M, Akin E, Gumustas FO (2012) The association of tattooing/body piercing and psychopathology in adolescents: a community based study from Istanbul. Commun Ment Health J 48(6):798–803 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Eubanks V (1996) Zones of Dither: writing the postmodern body. Body Soc 2(3):73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034×96002003004ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Ferguson-Rayport SM, Griffith RM, Straus EW (1955) The psychiatric significance of tattoos. Psychiatric Q 29(1):112–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01567443ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Flanagan JL, Lewis VJ (2019) Marked inside and out: an exploration of perceived stigma of the tattooed in the workplace. Equal, Divers Inclus Int J, 38(1):87-106. https://doi.org/10.1108/EDI-06-2018-0101

- Forbes GB (2001) College students with tattoos and piercings: Motives, family experiences, personality factors, and perception by others. Psychol Rep 89(3):774. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.2001.89.3.774ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Funk F, Todorov A (2013) Criminal stereotypes in the courtroom: Facial tattoos affect guilt and punishment differently. Psychol Public Policy Law 19(4):466 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Galbarczyk A, Mijas M, Marcinkowska UM, Koziara K, Apanasewicz A, Ziomkiewicz A (2020) Association between sexual orientations of individuals and perceptions of tattooed men. Psychol Sex 11(3):150–160 Google Scholar

- Galbarczyk A, Ziomkiewicz A (2017) Tattooed men: healthy bad boys and good-looking competitors. Pers Individ Differs 106:122–125 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Geller S, Magen E, Levy S, Handelzalts J (2020) Inkskinned: gender and personality aspects affecting heavy tattooing—a moderation model. J Adult Dev 27(3):192–200 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Govenar A (2000) The changing image of tattooing in American culture, 1846-1966. In: Caplan J (ed.), Written on the body: the tattoo in European and American history. Princeton University Press. p. 212

- Guéguen N (2012a) Tattoos, piercings, and alcohol consumption. Alcoholism: Clin Exp Res 36(7):1253–1256 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Guéguen N (2012b) Tattoos, piercings, and sexual activity. Soc Behav Pers: Int J 40(9):1543–1547 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Guéguen N (2013) Effects of a tattoo on men’s behavior and attitudes towards women: an experimental field study. Arch Sex Behav 42(8):1517–1524 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hauke-Forman N, Methner N, Bruckmüller S (2021) Assertive, but less competent and trustworthy? perception of police officers with tattoos and piercings. J Police Criml Psychol 36(3):523–536 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hawkes D, Senn CY, Thorn C (2004) Factors that influence attitudes toward women with tattoos. Sex Roles 50(9):593–604 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Hill BM, Ogletree S, McCrary K (2016) Body modifications in college students: considering gender, self-esteem, body appreciation, and reasons for tattoos. Coll Stud J 50(2):246–252 Google Scholar

- Howson A (2013) The body in society: an introduction. John Wiley & Sons

- Huxley C, Grogan S (2005) Tattooing, piercing, healthy behaviours and health value. J Health Psychol 10(6):831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105305057317ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jaworska K, Fijałkowska M, Antoszewski B (2018) Tattoos yesterday and today in the Polish population in the decade 2004–2014. Health Psychology Report 6(4):321–329 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Jelinski J (2018) Bad bastards? tattooing, health, and regulation in twentieth-century vancouve. Urban Hist Rev/Revue d’histoire urbaine 47(1/2):103–114. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26841717Google Scholar

- Jennings WG, Fox BH, Farrington DP (2014) Inked into crime? An examination of the causal relationship between tattoos and life-course offending among males from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. J Crim Just 42(1):77–84 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kalanj-Mizzi SA, Snell TL, Simmonds JG (2019) Motivations for multiple tattoo acquisition: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Adv Men Health 17(2):196–213 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kertzman S, Kagan A, Hegedish O, Lapidus R, Weizman A (2019a) Do young women with tattoos have lower self-esteem and body image than their peers without tattoos? A non-verbal repertory grid technique approach. PLoS ONE 14(1):e0206411 ArticleCASGoogle Scholar

- Kertzman S, Kagan A, Hegedish O, Lapidus R, Weizman A (2019b) The role of inhibition capacities in the Iowa gambling test performance in young tattooed women. BMC Psychol 7(1):1–9 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kertzman S, Kagan A, Vainder M, Lapidus R, Weizman A (2013) Interactions between risky decisions, impulsiveness and smoking in young tattooed women. BMC Psychiatry 13(1):1–8 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kluger N (2015) Epidemiology of tattoos in industrialized countries. Curr Prob Dermatol 48:6. https://doi.org/10.1159/000369175ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kluger N, Koljonen V (2012) Tattoos, inks, and cancer. Lancet Oncol 13(4):e161. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(11)70340-0ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Koch JR, Roberts AE, Armstrong ML, Owen DC (2005) College students, tattoos, and sexual activity. Psychol Rep 97(3):887–890 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Koch JR, Roberts AE, Cannon JH, Armstrong ML, Owen DC (2005) College students, tattooing, and the health belief model: extending social psychological perspectives on youth culture and deviance. Sociol Spectr 25(1):79–102 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Kruglanski AW, Wolfgang S (2012). The making of social psychology. In: Handbook of the history of social psychology. Psychology Press. pp. 3–17

- Lane DC (2014) Tat’s all folks: an analysis of tattoo literature. Sociol Compass 8(4):398–410 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lingel J, Boyd D (2013) “Keep it secret, keep it safe”: information poverty, information norms, and stigma. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 64(5):981–991. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22800ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Lodder M (2013) Neo-Victorian tattooing. Victoriana: a miscellany. Guildhall Art Gallery, London, p 105–112 Google Scholar

- Lynn CD, Medeiros CA (2017) Tattooing commitment, quality, and football in Southeastern North America. In: Lynn CD, Glaze AL, Evans WA, Reed LK (eds.). Evolution education in the American South. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 263

- Lynn CD, Puckett T, Guitar A, Roy N (2019) Shirts or skins?: Tattoos as costly honest signals of fitness and affiliation among US intercollegiate athletes and other undergraduates. Evol Psychol Sci 5:151–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-018-0174-4ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Manuel L, Retzlaff PD (2002) Psychopathology and tattooing among prisoners. Int J Offender Ther Comparat Criminol 46(5):522–531 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Martin A (1997) On teenagers and tattoos. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(6):860–861. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199706000-00025

- Martino S (2008) Perceptions of a photograph of a woman with visible piercings. Psychol Rep 103(1):134–138 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Martino S, Lester D (2011) Perceptions of visible piercings: a pilot study. Psychol Rep 109(3):755–758 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Maxwell D, Thomas J, Thomas SA (2020) Cathartic ink: a qualitative examination of tattoo motivations for survivors of sexual trauma. Deviant Behav 41(3):348–365 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- McCabe M (1997) New York City tattoo: The oral history of an urban art. Hardy Marks Publications

- Miłkowska K, Ziomkiewicz A, Galbarczyk A (2018) Tattooed man: could menstrual cycle phase and contraceptive use change female preferences towards bad boys. Pers Individ Differ 121(Supplement C):41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.017ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Molloy K, Wagstaff D (2021) Effects of gender, self-rated attractiveness, and mate value on perceptions tattoos. Pers Individ Differ 168:110382 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mortensen K, French MT, Timming AR (2019) Are tattoos associated with negative health‐related outcomes and risky behaviors? Int J Dermatol 58(7):816–824 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Mun JM, Janigo KA, Johnson KK (2012) Tattoo and the self. Cloth Text Res J 30(2):134–148 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Naudé L, Jordaan J, Bergh L (2019) “My body is my journal, and my tattoos are my story”: South African psychology students’ reflections on tattoo practices. Curr Psychol 38(1):177–186 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Oettermann S (2000) On display: tattooed entertainers in America and Germany. In: Caplan J (ed.). Written on the body: the tattoo in European and American history. Princeton University Press. pp. 193

- Pajor AJ, Broniarczyk-Dyła G, Świtalska J (2015) Satisfaction with life, self-esteem and evaluation of mental health in people with tattoos or piercings. Psychiatria Polska 49(3):559–573 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Phillips M (2022) Seeing tattoos makes me feel physically sick: Ubiquity of body art is born out of an existential crisis of humanity in the post-religious world. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/seeing-tattoos-makes-me-feel-physically-sick-6gxpjv85t

- Pirrone C, Castellano S, Platania GA, Ruggieri S, Caponnetto P (2020) Comparing the emerging psychological meaning of tattoos in drug-addicted and not drug-addicted adults: a look inside health risks. Health Psychol Res 8(2):9268. https://doi.org/10.4081/hpr.2020.9268

- Pitts-Taylor V (2003) In the flesh: The cultural politics of body modification. Palgrave Macmillan. http://scout.lib.ua.edu/?itemid=library/m/voyager1568152

- Resenhoeft A, Villa J, Wiseman D (2008) Tattoos can harm perceptions: a study and suggestions. J Am Coll Health 56(5):593. https://doi.org/10.3200/jach.56.5.593-596ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Roberti JW, Storch EA (2005) Psychosocial adjustment of college students with tattoos and piercings. J College Counsel 8(1):14–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2005.tb00068.xArticleGoogle Scholar

- Roberts TA, Auinger P, Ryan SA (2004) Body piercing and high-risk behavior in adolescents. J Adolesc Health 34(3):224–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.06.005ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Rubin A (1988) The tattoo renaissance. In: Rubin A (ed.). Marks of civilization: artistic transformations of the human body. University of California Museum of Cultural History. p. 233

- Ruffle BJ, Wilson AE (2019) Tat will tell: tattoos and time preferences. J Econ Behav Organ 166:566–585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2019.08.001ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sagoe D, Pallesen S, Andreassen CS (2017) Prevalence and correlates of tattooing in Norway: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Scand J Psychol 58(6):562–570. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12399ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Scheinfeld N (2007) Tattoos and religion. Clinics in dermatology 25(4):362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.05.009ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Schlösser A, Giacomozzi AI, Camargo BV, Silva EZPD, Xavier M (2020) Mujeres con Tatuajes y sin Tatuajes: Motivaciones, Prácticas Sociales y Comportamiento de Riesgo. Psico-USF 25(1):51–62 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Seiter JS, Hatch S (2005) Effect of tattoos on perceptions of credibility and attractiveness. Psychol Rep 96(3_suppl):1113–1120 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Sheridan CL, Radmacher SA (1992) Health psychology: Challenging the biomedical model. John Wiley & Sons

- Skegg K, Nada-Raja S, Paul C, Skegg DC (2007) Body piercing, personality, and sexual behavior. Arch Sex Behav 36(1):47–54 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Skoda K, Oswald F, Brown K, Hesse C, Pedersen CL (2020) Showing skin: Tattoo visibility status, egalitarianism, and personality are predictors of sexual openness among women. Sex Cult 24(6):1935–1956 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Solís-Bravo MA, Flores-Rodríguez Y, Tapia-Guillen LG, Gatica-Hernández A, Guzmán-Reséndiz M, Salinas-Torres LA, Vargas-Rizo TL, Albores-Gallo L (2019) Are tattoos an indicator of severity of non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents? Psychiatry Investig 16(7):504 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stangor C (2014) Defining social psychology: history and principles. Principles of social psychology-1st International edn. BCcampus Open Education

- Stirn A, Hinz A (2008) Tattoos, body piercings, and self-injury: Is there a connection? Investigations on a core group of participants practicing body modification. Psychother Res 18(3):326–333 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stirn A, Hinz A, Brahler E (2006) Prevalence of tattooing and body piercing in Germany and perception of health, mental disorders, and sensation seeking among tattooed and body-pierced individuals. J Psychosomat Res 60(5):531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.09.002ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Stirn A, Oddo S, Peregrinova L, Philipp S, Hinz A (2011) Motivations for body piercings and tattoos —the role of sexual abuse and the frequency of body modifications. Psychiatry Res 190(2):359–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.06.001ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swami V (2011) Marked for life? A prospective study of tattoos on appearance anxiety and dissatisfaction, perceptions of uniqueness, and self-esteem. Body Image 8(3):237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.005ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swami V (2012) Written on the body? Individual differences between British adults who do and do not obtain a first tattoo. Scand J Psychol 53(5):407–412 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swami V, Gaughan H, Tran US, Kuhlmann T, Stieger S, Voracek M (2015) Are tattooed adults really more aggressive and rebellious than those without tattoos? Body Image 15:149–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.09.001ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swami V, Pietschnig J, Bertl B, Nader IW, Stieger S, Voracek M (2012) Personality differences between tattooed and non-tattooed individuals. Psychol Reports 111(1):97–106. https://doi.org/10.2466/09.07.21.Pr0.111.4.97-106ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Swami V, Tran US, Kuhlmann T, Stieger S, Gaughan H, Voracek M (2016) More similar than different: tattooed adults are only slightly more impulsive and willing to take risks than Non-tattooed adults. Pers Individ Differ 88:40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.08.054ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tate JC, Shelton BL (2008) Personality correlates of tattooing and body piercing in a college sample: the kids are alright. Pers Individ Differ 45(4):281–285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.04.011ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Taylor AJ (1974) Criminal tattoos. Int Rev Appl Psychol 23(2):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.1974.tb00313.xArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tews MJ, Stafford K, Kudler EP (2020) The influence of tattoo content on perceptions of employment suitability across the generational divide. J Pers Psychol 19(1):4–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/1866-5888/a000234ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Thielgen MM, Schade S, Rohr J (2020) How criminal offenders perceive police officers’ appearance: effects of uniforms and tattoos on inmates’ attitudes. J Forens Psychol Res Pract 20(3):214–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1714408ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Thomas JN, Copulsky D (2021) Diversifying conceptions of sexual pleasure in self-reported genital piercing stories. Deviant Behav 42(8):1032–1042. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2020.1718834ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Thompson K (2015) Comparing the psychosocial health of tattooed and non-tattooed women. Pers Individ Differ 74:122–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.10.010ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tiggemann M, Golder F (2006) Tattooing: an expression of uniqueness in the appearance domain. Body Image 3(4):309–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.09.002ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Tiggemann M, Hopkins LA (2011) Tattoos and piercings: bodily expressions of uniqueness? Body Image 8(3):245–250 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Timming A, Nickson D, Re D, Perrett D (2017) What do you think of my ink? Assessing the effects of body art on employment chances. Human Resour Manag: published in cooperation with the School of Business Administration, The University of Michigan and in alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management 56(1):133–149. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21770ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Timming AR (2015) Visible tattoos in the service sector: a new challenge to recruitment and selection. Work Employm Society 29(1):60–78 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Timming AR (2017) Body art as branded labour: at the intersection of employee selection and relationship marketing. Hum Relat 70(9):1041 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Timming AR, Perrett D (2016) Trust and mixed signals: a study of religion, tattoos and cognitive dissonance. Pers Individ Differ 97:234–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.067ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Vale V, Juno A (eds.) (1989). Modern primitives: an investigation of contemporary adornment and ritual. RE/Search Publications

- Vizgaitis AL, Lenzenweger MF (2019) Pierced identities: body modification, borderline personality features, identity, and self-concept disturbances. Pers Disord Theor Res Treatment 10(2):154 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wasarhaley NE, Vilk RF (2020) More than skin deep? The effect of visible tattoos on the perceived characteristics of a rape victim. Women Crim Just 30(2):106–125 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Willman JC, Hernando R, Matu M, Crevecoeur I (2020) Biocultural diversity in Late Pleistocene/Early Holocene Africa: Olduvai Hominid 1 (Tanzania) biological affinity and intentional body modification. Am J Phy Anthropol 172(4):664–681. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.24007ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wiseman DB (2010a) Patient characteristics that impact tattoo removal resource‐allocation choices: tattoo content, age, and parental status. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(11):2736–2749 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wiseman DB (2010b) Perceptions of a tattooed college instructor. Psychol Rep 106(3):845–850 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wohlrab S, Fink B, Kappeler PM, Brewer G (2009a) Differences in personality attributions toward tattooed and nontattooed virtual human characters. J Individ Differ 30(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001.30.1.1ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Wohlrab S, Fink B, Kappeler PM, Brewer G (2009b) Perception of human body modification. Pers Individ Differ 46(2):202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.09.031ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zestcott CA, Bean MG, Stone J (2017) Evidence of negative implicit attitudes toward individuals with a tattoo near the face. Group Process Intergroup Relat 20(2):186–201 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zestcott CA, Stone J (2019) Experimental evidence that a patient’s tattoo increases their assigned health care cost liability. Stigma Health 4(4):442 ArticleGoogle Scholar

- Zestcott CA, Tompkins TL, Kozak Williams M, Livesay K, Chan KL (2018) What do you think about ink? An examination of implicit and explicit attitudes toward tattooed individuals. J Soc Psychol 158(1):7 ArticleGoogle Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Psychology, University of Sunderland, Sunderland, SR13SD, UK Rebecca Owens

- Department of Anthropology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, 19122, USA Steven J. Filoromo

- Department of Anthropology, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, 35487, USA Steven J. Filoromo, Christopher D. Lynn & Michael R. A. Smetana

- Department of Philosophy, University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, AL, 35487, USA Lauren A. Landgraf

- Rebecca Owens